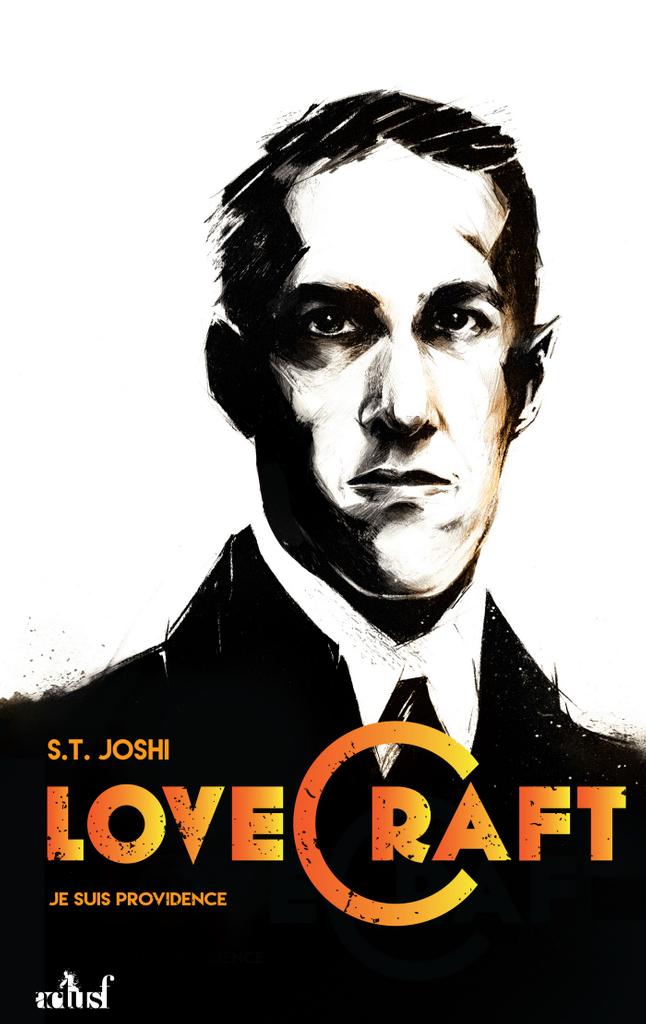

Salutations, lecteur. Aujourd’hui, j’ai l’immense plaisir de te proposer une interview de S. T. Joshi, spécialiste mondial de H. P. Lovecraft et entre autres auteur de la biographie Je suis Providence, parue récemment chez ActuSF.

L’article que vous lisez actuellement est la version originale de l’interview, en anglais. Une version traduite en français est également disponible.

Je vous rappelle que vous pouvez retrouver toutes les autres interviews en suivant ce tag, mais aussi dans la catégorie « Interview » dans le menu du blog.

Je remercie très chaleureusement S. T. Joshi d’avoir répondu à mes questions, et sur ce, je lui laisse la parole !

Interview of S. T. Joshi

Marc: Could you introduce yourself for readers who may not know you and your work?

S. T. Joshi: I am S. T. Joshi (b. 1958). I was born in India but came to the United States when I was 5. I am a leading authority in H. P. Lovecraft and have prepared corrected editions of his collected fiction, essays, poetry, and letters. I have also done scholarly work on other authors of weird fiction, including Lord Dunsany, Ambrose Bierce, Arthur Machen, and Ramsey Campbell. I have also done work on the American journalist H. L. Mencken. Among my critical and biographical studies are The Weird Tale (1990), The Modern Weird Tale (2001), I Am Providence: The Life and Times of H. P. Lovecraft (2010), and Unutterable Horror: A History of Supernatural Fiction (2012).

Marc: When did you discover H. P. Lovecraft? How did you first discover his work?

S. T. Joshi: I must have been about 13 or 14 when I first read Lovecraft. I came upon a little paperback anthology called 11 Great Horror Stories (1969), edited by Betty Owen. It contained “The Dunwich Horror.” I remember the haunting atmosphere of rural New England in that tale—very different from what I was familiar with, as my family had settled in the Midwest (Illinois, and later Indiana) of the United States. Later I found the Arkham House volumes of Lovecraft’s stories in my public library, and became fascinated with both his work and his life. I attended Brown University chiefly to study Lovecraft: I knew that his papers were in the library there, and I also wished to absorb the atmosphere of his native city (Providence, Rhode Island). The six years in Providence changed my life and made me the writer and scholar that I am today.

Marc: Why did you decide to study him and other authors of the horror genre from the early 20th century, such as Ambrose Bierce, Algernon Blackwood, Lord Dunsany or Arthur Machen?

S. T. Joshi: At the time I became interested in Lovecraft (early 1970s), very little scholarly work had been done on him. But a new group of scholars were emerging who were studying Lovecraft far more deeply than before. The leader of this group was Dirk W. Mosig, a professor in Georgia; and he quickly became my mentor, helping me to understand the complexities of Lovecraft’s fiction and the value of studying his life and philosophical outlook. From Lovecraft himself I became interested in other writers of weird fiction who influenced him—Poe, Machen, Dunsany, Blackwood, and others. I saw that it is extremely important to place Lovecraft in the context of his times—both in the history of weird fiction and in the political, social, and cultural history of the United States during his lifetime.

Marc: What was your academic approach to Lovecraft’s fiction and to the other authors of supernatural horror when you studied them as a scholar?

S. T. Joshi: At Brown University I did not study English or American literature extensively; instead, I became fascinated with the literature of Greece and Rome, and also with ancient history and philosophy. (This interest was initially sparked by Lovecraft himself, because he had been interested in these subjects and I wished to know what significance they had for him.) The study of classical literature relies on a careful study of the text (what is called “close reading”) as well as the historical context in which it was written. I have used these same principles in the study of Lovecraft and other writers, and have always found it a good way to approach them.

Marc: You are considered a specialist of weird and fantastic fiction. How are these kinds of literature perceived in the United States? How would you define Lovecraft’s American public? Has the public evolved?

S. T. Joshi: For centuries in the United States, weird fiction was not considered to be genuine literature. It was regarded as “escapist” fiction written for the masses, as distinguished from the literature of social realism and other forms of “high” art. This attitude was particularly prevalent in Lovecraft’s own day, when the Modernists (T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, James Joyce, etc.) championed realism and scorned fantasy and the supernatural. As a result, Lovecraft and other writers faced a great deal of prejudice from the literary mainstream. This was compounded by the fact that Lovecraft’s tales first appeared in “pulp” magazines such as Weird Tales. But over the past several decades there has been a revolution in our understanding of the literary value of this kind of literature. Science fiction first became “respectable” in the 1960s, and weird fiction followed a little later. I hope I have had some influence in demonstrating how Lovecraft himself can be regarded as “high” literature, given his meticulous attention to language, the profound conceptions underlying his tales, and other factors. At the same time, Lovecraft has become an immensely popular writer, and his work has now been adapted into films, comic books, computer games, and many other media. There are virtually no writers in the entire range of world literature who appeal to such a diverse body of readers as Lovecraft.

Marc: How are the weird and fantastic literature perceived by American academics? How do they perceive Lovecraft, Dunsany, Blackwood, or Machen?

S. T. Joshi: American academics have somewhat grudgingly acknowledged Lovecraft as a significant writer. When a volume of his tales appeared in the Library of America (2005), which publishes the leading writers in the entire range of American literature, most critics welcomed his inclusion; but some complained that Lovecraft did not deserve to be published by such a prestigious publisher. Even now, there are a few academics who still question the greatness of Edgar Allan Poe. And there is very little academic attention devoted to Dunsany, Blackwood, or Machen. Even Ambrose Bierce is of interest to academics only because of his involvement in the American Civil War and his writings about that conflict. So American academics still have a long way to go in the appreciation of weird fiction!

Marc: You have established the critical and definitive editions of Lovecraft’s stories. Could you describe your process in establishing the Lovecraftian corpus in those critical editions?

S. T. Joshi: When I came to Brown University in 1976 and began examining the manuscripts of Lovecraft’s tales housed in its library, I was appalled by the extent to which typographical and other errors filled the standard Arkham House editions of his stories. The training I was receiving in classical literature made me realise that I had to ascertain the sources for these errors by studying each publication of a given story to determine how these errors had crept into the text. It took me years to prepare corrected editions of the stories. Then I approached Arkham House, and eventually we agreed that my texts would serve as the basis of new editions, which came out in 3 volumes in 1984–86. These texts have now been used in many other editions, including my annotated Penguin editions, the Library of America edition, and elsewhere. Recently I edited Lovecraft’s Complete Fiction: A Variorum Edition (Hippocampus Press, 2015–17; 4 volumes), in which I specify all the textual variants in Lovecraft’s stories.

Marc: In I Am Providence, your Lovecraft biography, you debunked myths about the author, such as for example his supposed lack of social interaction and skills. Do these myths still persist today? And if so, why?

S. T. Joshi: As I studied Lovecraft’s life, I found that at least some of the myths surrounding Lovecraft were to some extent fostered by Lovecraft himself. It was he who liked to think of himself as an “old man” who wrote only at night and slept during the day, who was a “recluse” who rarely ventured out of his house, etc. I think Lovecraft fostered these myths in a spirit of fun, but they were seized upon by later critics to portray him as an eccentric whose work did not deserve attention in its own right. I find that some of these myths are still prevalent, although I believe many of them have now been overthrown. And yet, it is difficult to prevent them from springing up in unexpected places—it is rather like “fake news”!

Marc: How does the American public perceive Lovecraft and his work today? Would you say that his personality or his stories are a source of controversy? For example, how do people perceive his racism, which can sometimes be read in the work?

S. T. Joshi: Although Lovecraft is popular in the United States (and around the world), and he is being read more and more widely, the belief that Lovecraft was a “vicious racist” is having a damaging effect on his reputation. This belief is often fostered by people who have a low regard for Lovecraft and have seized upon this one flaw in his character in order to discredit his work as a whole. These people are not interested in truly understanding why Lovecraft adopted the views he did, or what historical or personal circumstances led him to do so; they simply use racism as a cudgel to beat Lovecraft over the head with. I myself, as a person of colour, have never felt any personal insult in Lovecraft’s racism and have always believed that it was an unfortunate result of his personal circumstances and of the culture in which he lived. And racism has relatively little effect on his greatest works of fiction.

Marc: What is your favorite Lovecraft story, and why? Which do you dislike the most ?

S. T. Joshi: I have always regarded At the Mountains of Madness as his greatest story: its conclusion, when the human characters encounter the monstrous shoggoth, strikes me as one of the most chilling passages in the entire history of literature. But it is a difficult text to read, and not something that the novice reader should start with. One of my least favourite Lovecraft stories is “The Horror at Red Hook”—not chiefly because it is a racist story, but because it uses all manner of hackneyed motifs of supernatural literature, and is in fact a confused and incoherent piece of work.

Marc: How do you explain the large amount of correspondence that Lovecraft wrote in his life, and what role do you attribute it in his oeuvre? You write in I Am Providence that Lovecraft could be more well known for his letters in the future than he is for his stories today. Why?

S. T. Joshi: Lovecraft used correspondence as a form of socialising: it was his way of communicating with people whom he found interesting. There were simply not very many people in Providence who shared his views or interests, and so he had to find them all across the country. I also think there was an element of autism in Lovecraft, in that he seemed unable to prevent himself from writing immense letters to relative strangers about the most intimate aspects of his life and beliefs. But those letters, written with incredible elegance and panache, are so full of fascinating discussions of philosophy, literature, culture, and many other subjects that they become literary documents in their own right. They reveal the full range of Lovecraft’s mind and character, whereas his stories and poems only reveal certain limited aspects of them.

Marc: In I Am Providence, you use documents such as the amateur journalistic publications of Lovecraft, his correspondences, as well as his school and medical reports. Did you have trouble finding these documents?

S. T. Joshi: It is fortunate that I had been studying Lovecraft for nearly twenty years prior to actually beginning the writing of I Am Providence (I wrote it in 1993–95; an abridged version, H. P. Lovecraft: A Life, was published in 1996, and the full version appeared in 2010). During these years I had gathered many of the documents I needed to write the biography. But even so, I had to do considerable work in tracking down other documents. But the chief difficulty was not actually finding the documents but in coordinating this immense body of information in order to make a coherent portrait of Lovecraft from the beginning of his life to its end.

Marc: You are currently working on a complete edition of Lovecraft’s letters. How would you describe this work? What can Lovecraft’s correspondence teach us about him?

S. T. Joshi: My edition of Lovecraft’s correspondence (in which I am collaborating with David E. Schultz) will present every surviving letter of Lovecraft in unabridged form, and with suitable annotations. The edition will fill at least 25 volumes. (There may be more letters out there that I have not located!) When completed, this edition will present the fullest possible portrait of Lovecraft the man, the writer, and the thinker. The volumes are arranged in such a way that all the letters to a single correspondent are presented in sequence, so that one can gauge the development of his relations with that correspondent over time. It is fascinating to see how Lovecraft adapts his letters to the person he is writing to, always taking an interest in what they have to say. Each letter offers some little bit of information we did not know before, and this body of work will lay the foundation for a proper understanding of the rest of his work.

Marc: How would you define Lovecraft’s influence on horror, science-fiction and fantasy literature, as well as on other arts such as visual arts, with artists like H. R. Giger?

S. T. Joshi: Lovecraft’s influence on subsequent literature has been immense—and is constantly growing. Initially, he influenced only a small number of writers (many of them his own colleagues) who wrote “tales of the Cthulhu Mythos” in imitation of his own stories. Many of these imitations were quite unimaginative and formulaic, but today we have writers—ranging from Ramsey Campbell to Caitlín R. Kiernan to Jonathan Thomas—who are writing works that more profoundly draw upon the essence of Lovecraft’s fiction (his “cosmic” perspective; his fascination with weird landscape; his interest in degeneration, etc.) to write tales that are of aesthetic value in themselves. Lovecraft’s influence on science fiction is still not well examined, but he has left his mark on such writers as Arthur C. Clarke, Philip K. Dick, and others. And now Lovecraftian elements can be found in many films, even those that are not explicit adaptations of Lovecraft’s own stories. Alien (1979) is without doubt one of the most powerful “Lovecraftian” films every made; and several others of this sort can be cited. Lovecraft has indeed influenced a wide array of pictorial artists—and has even left his mark on heavy metal music!

Marc: You published the anthologies entitled Black Wings of Cthulhu, which collect stories inspired by Lovecraft’s work. Could you tell me about your selection process for these stories? Did you openly call for submissions, or did the authors contact you? In your opinion, how do the stories of Black Wings stand out with regards to other texts and authors descended to Lovecraft like August Derleth? Have you read any French Lovecraftian stories?

S. T. Joshi: In 2008 I wrote a treatise called The Rise and Fall of the Cthulhu Mythos, in which I examined both Lovecraft’s “Cthulhu Mythos” tales and those by others. I had expected the work of Lovecraft’s imitators to be uniformly mediocre, but to my surprise I found at least some of it to be quite good. I had by this time established contact with some of the leading writers in the weird fiction field, including Caitlín R. Kiernan and Ramsey Campbell; and so I contacted about 20 of them and asked them to write “Lovecraftian” stories—not stories that mechanically imitated Lovecraft’s own stories, but used the conceptions in his stories as a springboard for tales expressing the author’s point of view. I was extremely gratified by receiving outstanding tales by Kiernan, Jonathan Thomas, Laird Barron, W. H. Pugmire, and several others for the first Black Wings volume. I did not wish to have an “open” submission policy, as I did not wish to read hundreds of submissions by writers I did not know; instead, I specifically asked writers to send me a contribution. Over the years I have expanded my range of contacts to include such writers as Steve Rasnic Tem, Nancy Kilpatrick, John Reppion, and many others. After compiling six volumes of the Black Wings series, I am now taking a little break; but I have finished an anthology entitled His Own Most Fantastic Creation, which includes stories using Lovecraft (or a Lovecraft-like figure) as a character. This volume will come out in 2020 from PS Publishing.

Marc: Do you have any anecdotes related to your research on Lovecraft and other horror authors? What are your best memories as a scholar?

S. T. Joshi: Many people are surprised at how much I have done over the years, with many editions of works by Lovecraft and other writers, critical and biographical studies, essays, reviews, etc. But much of the groundwork for this edition was done early in my career. While pursuing a Ph.D. at Princeton (1982–84), I found that the library there contained a large number of British and American periodicals, and I photocopies huge masses of stories, essays, and other work by Machen, Dunsany, and other writers. When I worked for a publishing company in New York, Chelsea House (1984–95), I often did some personal research on “company time,” going to the New York Public Library and looking up material relating to Ambrose Bierce, the poet George Sterling, and other writers. Sometimes the research lies dormant in my files for decades—until I suddenly find the opportunity to make use of it. So this accounts for why I seem to be able to complete a book in a fairly short time. I actually enjoy doing the research for a volume more than doing the actual writing for the volume. I am tremendously forunate in being able to do this kind of work full time. I am, in effect, doing exactly what I wish to do in my life.

Great interview…essential questions and into the point answers, I have just started reading Joshi’ s books on weird literature hoping to do the same with Arabic weird fiction..who knows?

J’aimeAimé par 1 personne

Thanks a lot! 🙂

Wow, Arabic weird fiction is very interesting ! 🙂

J’aimeJ’aime